I am seven. We live on food stamps. I get free school lunch, things like sloppy joes and crumbly peanut butter sandwiches. My clothing comes from the Salvation Army. We are told over and over that we cannot have any toys that need batteries, as batteries cost money we do not have. In summer, we go to the local pool almost every day - chugging along on a single lane dirt road in my mother’s rusting Dodge Dart. The radio is always tuned to an AM station. The songs tumble out, magnificent little dustbowl operas like Wichita Lineman. My young brain begins to understand that Glen Campbell is quite a person. I don’t care if he wrote the lyrics or not, no matter how delicious and broken those words are. It is his voice, his understanding of the universe, his world-weariness and that underbelly of romance exposed on those crappy speakers that makes my ears burn.

“This is a freaking SONG.” I thought to myself, every time he came on.

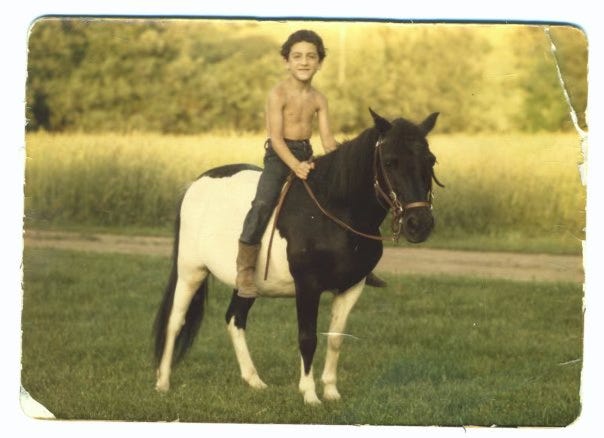

I don’t know how we had that pony. His name was Patches, and he often ran away. We never got a saddle on him, just a bridle bought at a garage sale. I rode him sometimes, a long slow circle around our mammoth driveway. I had cowboy boots from a garage sale too, or maybe they were sent in a box of clothes from relatives I have never met. They were pointy, and took forever to pull on but they sure made me feel like someone.

I did a lot of squinting back then. I thought that was what cowboys did, looking tough at the horizon, knowing nothing much but enough to get to tomorrow.

A hundred million years later, I sit in the living room looking out at the blue-going-purple mountains beyond our windows in Tbilisi. The balcony door and windows are flung open, as the smell of cherry blossoms and lilacs flood the city. An old guitar leans against me. It is over 100 years old. I have found the chords to one of those songs, and somehow I can sing it. There is something that happens when you sing something you have held dear for the bulk of your life. You speak across decades, howling at the walls, pushing air from behind those wrinkles, your belly a few sizes too large, your voice frail and weathered, and on a good day, half-wise. There is a Japanese term “mono no aware” it means many things, and it describes this moment so perfectly. The awareness of impermanence, the pathos of things and a sadness at their passing. They often use it to describe cherry blossoms, so I am simply in the right place and right time. Even a broken clock is right two times a day.

I tried to record Rhinestone Cowboy and was convinced I had failed, my fingertips shivering, they were so tired. I can’t seem to keep the callouses on them, those rough lumps of skin that let me press the strings right. Something always seems to get in the way. But here I am, giving it my hail Mary shot because that is the only way things happen these days.

Thanks for listening.

Share this post